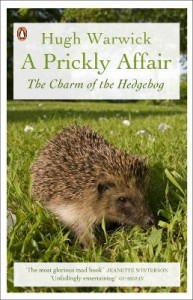

Although you may not have spent much time contemplating the character of hedgehogs and our relationship with them, I know a man who has. Ecologist Hugh Warwick is the author of a brilliantly funny and engaging book called A Prickly Affair: The Charm of the Hedgehog, which has just come out in paperback, receiving rave reviews in The Guardian and elsewhere. I spoke with him about his mania for hedgehogs and what his researches around the world – he tracked down a hedgehog in China named Hugh and attended the International Hedgehog Olympic Games in the Rocky Mountains – reveal about our understanding of human empathy with animals. Continue reading

Although you may not have spent much time contemplating the character of hedgehogs and our relationship with them, I know a man who has. Ecologist Hugh Warwick is the author of a brilliantly funny and engaging book called A Prickly Affair: The Charm of the Hedgehog, which has just come out in paperback, receiving rave reviews in The Guardian and elsewhere. I spoke with him about his mania for hedgehogs and what his researches around the world – he tracked down a hedgehog in China named Hugh and attended the International Hedgehog Olympic Games in the Rocky Mountains – reveal about our understanding of human empathy with animals. Continue reading

The Empathy Top Five: Who are the greatest empathists of all time?

The moment has finally come for the Outrospection blog to put its cards on the table and boldly declare who are the greatest empathists of all time. Our selection committee has been painstakingly deliberating over the choices for several months, and you might well be surprised by the results. No, Barack Obama does not appear in our top five, even though he believes ‘the empathy deficit’ to be the greatest scourge of modern society. And not even famed empathetic individuals such as the Dalai Lama, Mother Teresa or Jesus Christ have shown what it takes to make the grade. Continue reading

The view from the diving-bell

‘When I came to that late-January morning the hospital opthalmologist was leaning over me and sewing my right eyelid shut with a needle and thread, just as if he were darning a sock. Irrational terror swept over me.’ These words appear in Jean-Dominique Bauby’s remarkable autobiography, The Diving-Bell and the Butterfly (1997). In 1995 Bauby was at the height of his career as editor-in-chief of French Elle magazine, when he was suddenly struck by a massive stroke. Although his mental faculties were unimpaired, he was left completely paralysed and speechless, a rare condition known as Locked-In Syndrome. The only part of his body he could move was his left eyelid, which he used to ‘dictate’ the book, having developed a system of repeated blinks to represent each letter of the alphabet.

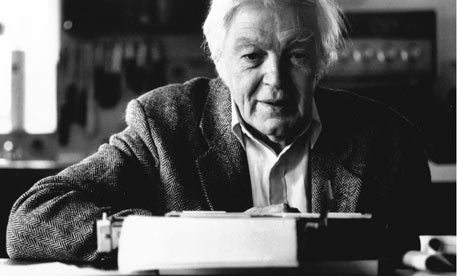

Continue readingColin Ward – an obituary and appreciation of the chuckling anarchist

Colin Ward was one the greatest anarchist thinkers of the past half century and a pioneering social historian. He died earlier this month at the age of eighty-five, leaving a legacy of over thirty books and a huge following of activists, educators and writers – amongst them myself – who were inspired by his approach to radical social change, which always favoured practical, grass-roots action over utopian dreamings of revolution. The outpouring of obituaries in The Guardian and elsewhere are testimony to his influence. Continue reading

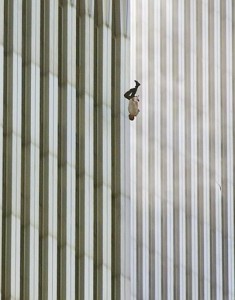

Ian McEwan on Love, Empathy and 9/11

Anybody who reads novels is a secret empathist. Most writers of fiction try to take you on a journey into the minds and lives of their characters, introducing you to worldviews that are not your own, filling your head with the voices of strangers. An instance from the history of empathetic literature is Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (1931), a story told from the perspective of five individuals, with all the dialogue and action being submerged in their thoughts. When we read books like The Waves, we are inevitably drawn to make the imaginative leap that is empathy.

Anybody who reads novels is a secret empathist. Most writers of fiction try to take you on a journey into the minds and lives of their characters, introducing you to worldviews that are not your own, filling your head with the voices of strangers. An instance from the history of empathetic literature is Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (1931), a story told from the perspective of five individuals, with all the dialogue and action being submerged in their thoughts. When we read books like The Waves, we are inevitably drawn to make the imaginative leap that is empathy.

I think novelists, who spend so much time attempting to understand the mental worlds of their protagonists, have a peculiar ability to appreciate the meaning and significance of empathy. One of the best examples of this is an article that Ian McEwan wrote in The Guardian, published just a few days after the September 11 attacks. It is, in effect, a meditation on empathy. ‘Imagining what it is like to be someone other than yourself is at the core of our humanity,’ he writes. ‘It is the essence of compassion, and it is the beginning of morality.‘ Here is the article in full. Continue reading

Reading the Mind in the Eyes

I’ve recently been involved in advising a fascinating BBC television series called Child of Our Time about how to measure empathy. This long-term project involves tracking the lives and development of 25 children from a range of social and ethnic backgrounds born in 2000, over a period of twenty years. The children are now ten, and the series currently in production aims to unveil the influences that shape their varying personality traits.

One of the empathy tests we discussed is called Reading the Mind in the Eyes, created by the Cambridge psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen, an expert on autism and author of a controversial book called The Essential Difference, which argues that women are more naturally empathetic than men. The test effectively gauges how good you are at judging someone’s emotional state through looking at their eyes. You are presented with 36 sets of eyes, and for each of them you are instructed to choose which one of four words best describes what the person in the picture is thinking or feeling. Continue reading

Should you empathise with your father's killer?

One of the greatest challenges of leading an empathetic life is trying to step into the shoes of people who we consider to be ‘enemies’ or whose views and values are very different from our own. If you’re on the receiving end of a racist comment from someone at the pub or a torrent of unfair verbal abuse from your boss, the idea of trying to empathise with them would probably be the last thing on your mind. If you came face to face with the person who had recently burgled your house, could you overcome your anger to see the crime from their perspective, and understand the circumstances that may have driven them to it?

Empathising in such instances might seem like wishful thinking. But consider the case of Jo Berry. Continue reading

Five ways to expand your empathy

It is usual, at this time of year, to make a series of earnest New Year’s Resolutions which – by tradition – you resolutely fail to keep. Why not try promising yourself some New Year’s Explorations instead and widen your personal horizons.

Expanding your empathy might offer just what you are looking for. Empathising is an avant-garde form of travel in which you step into the shoes of another person and see the world from their perspective. It is the ultimate adventure holiday – far more challenging than a bungee jump off Victoria Falls or trekking solo across the Gobi desert.

Here are my five top tips for transforming yourself into an empathetic adventurer over the coming months. Continue reading

Watch an empathy film this Christmas

Perhaps you are looking forward to falling asleep in front of a mediocre DVD on Christmas Day as you digest an oversized lunch. But if you care for a more stimulating afternoon, I can recommend treating yourself to an empathy film instead. So, what are the options?

A fascinating genre that can expand our empathetic imaginations is war movies depicting the perspective of enemies. Recent examples include a pair of films directed by Clint Eastwood in 2006 about the Battle for Iwo Jima in the Second World War, one from the viewpoint of US soldiers (Flags of Our Fathers), and the other seen through the eyes of Japanese soldiers (Letters from Iwo Jima), which is entirely in Japanese. The inverted lens challenges simplistic notions of nationalism, patriotism and triumphalism, and makes war seem far from glorious while at the same time breaking down the barriers between ‘us’ and ‘them’. Continue reading

Inside Obama’s Brain: In Conversation with Sasha Abramsky

Sasha Abramsky is one of the most original and politically insightful investigative journalists writing in the US today. He is best known for books such as Hard Times Blues, a penetrating critique of the US prison system, and Breadline USA, which reveals the hidden scandal of everyday hunger and poverty faced by American families. He is also a Senior Fellow at the New York City-based Demos think tank. His new book, Inside Obama’s Brain, attempts to delve inside the mind of the 44th President. I spoke to him about the book, and the central role that empathy plays in Obama’s political vision.

Sasha Abramsky is one of the most original and politically insightful investigative journalists writing in the US today. He is best known for books such as Hard Times Blues, a penetrating critique of the US prison system, and Breadline USA, which reveals the hidden scandal of everyday hunger and poverty faced by American families. He is also a Senior Fellow at the New York City-based Demos think tank. His new book, Inside Obama’s Brain, attempts to delve inside the mind of the 44th President. I spoke to him about the book, and the central role that empathy plays in Obama’s political vision.

Continue reading