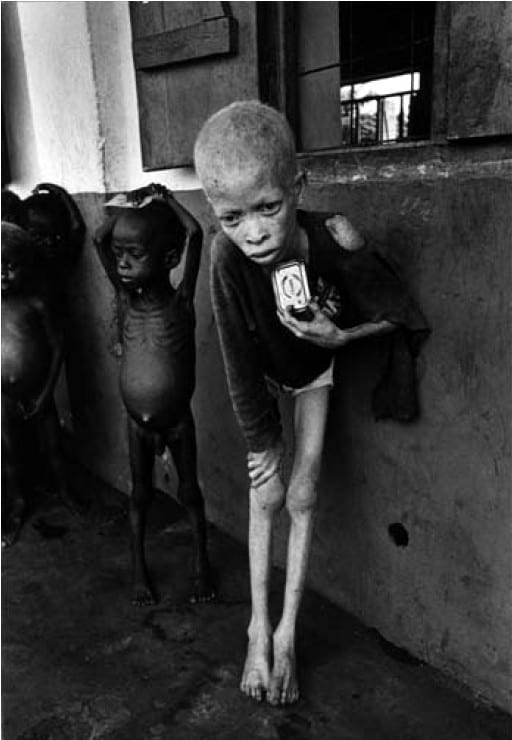

The British photojournalist Don McCullin has just turned seventy-five. During a career that has now spanned half a century, perhaps his most unforgettable photograph is of an emaciated albino boy in the Biafran War in Nigeria, taken in 1969. He is leaning over on skeletal legs with an abnormally large head, clutching an empty tin of corned beef. I have never seen an image like it and, at the time, neither had most of the Western world. Here is the photo:

In his autobiography Unreasonable Behaviour, McCullin describes his encounter with this boy, one of 800 war-orphaned children he discovered at a makeshift hospital:

As I entered I saw a young albino boy. To be a starving Biafran orphan was to be in a most pitiable situation, but to be a starving albino Biafran was to be in a position beyond description. Dying of starvation, he was still among his peers an object of ostracism, ridicule and insult…The boy looked at me with a fixity that evoked the evil eye in a way which harrowed me with guilt and unease. He was moving closer. He was haunting me, getting nearer. Someone was giving me the statistics of the suffering, the awful multiples of this tragedy. As I gazed at these grim victims of deprivation and starvation, my mind retreated to my own home in England where my children of much the same age were careless and cavalier with food, as Western children often are. Trying to balance between these two visions produced in me a kind of mental torment…I felt something touch my hand. The albino boy had crept close and moved his hand into mine. I felt tears come into my eyes as I stood there holding his hand. I thought, think of something else, anything else. Don’t cry in front of these kids…He looked hardly human, as if a tiny skeleton had somehow stayed alive…If I could, I would take this day out of my life, demolish the memory of it.

There was a massive empathic response to the suffering of the Biafran war – partly evoked by photos such as McCullin’s – leading to foreign intervention and an unprecedented international relief effort. But it is now more often the case that photos and statistics about people starving or massacred in distant countries do not provoke such a reaction. A common explanation is that we suffer from ‘compassion fatigue’ brought about by the barrage of depressing news stories and images from around the world. In her book On Photography, Susan Sontag described something akin to this when she wrote that ‘images anesthetize’: we have now seen too many photos of emaciated children for them to make a difference any more. We have become, in the words of Pink Floyd, comfortably numb.

For me, McCullin’s photo still has an extraordinary power. Not long ago, one evening around midnight, I was looking at the image of the albino boy on my computer screen. And suddenly his face morphed into that of my four-month-old son. There it was, his soft chubby cheeks and playful blue eyes balanced atop an emaciated and starving body, holding an empty tin of corned beef. My son’s face in that of a dying boy, a grotesque and distorted horror. A wave of nausea rose from my stomach and swept a shiver through my body. My palms were covered with sweat – as they are right now as I recall the sight.

It was a moment that opened me into a new kind of empathy. Since that night I have had a greater capacity to see the individuality in the faces of children I come across, whether it is a television image of an orphaned girl in Brazil or an eight-year-old at a bus stop in Oxford looking terribly sad and alone. Somehow I feel more alive to their sufferings, more aware of their identities. With help from Don McCullin, my own children have led me into the lives of others and helped expand my emotional lexis.

If you suffer from compassion fatigue, what might be your personal cure?

Hi,

To this day these images still move me and I hope are not forgotten in the minds and hearts of everyone. Perhaps, we remember these in despite the attempts of our own psyche in trying to move them from away from a place in our mind that continues to traumatize us.

You ask: ‘If you suffer from compassion fatigue, what might be your personal cure?’ and I answer in the only way that I can, which is from my own personal experience. This concept is also a topic close to my heart. I have worked with women from domestic violence situations and women and girls who have suffered sexual abuse and sexual violence for some time now. For the last eight years I have seen and witnessed how these incredible females have told, recovered, suffered, and sadly sometimes re-experienced their stories. This is perhaps a little closer to home to the topic that you write about, but it is by no means something that is experienced by women in the UK alone.

Like picture of the child above, which often strikes a pang of compassion and horror that such events do and can occur (and if we are all a honest probably some helplessness); these experiences of women can lead to a sense of feeling fatigued by ones own compassion, perhaps in the endlessness of it all. The well of ones heart is not endless shall we say and sometimes in such professions when you are continual exposed to these things you can find it running dry, or as you rightly state – we become comfortably numb to protect ourselves. I’d argue the ‘comfortably’ part, because I am sure that perhaps when we fully and consciously reconsider these things they still sicken us and provoke reactions namely …to do (to fight to feelings), to turn away (to avoid the pain of this), or to surrender (to experience the helplessness that these pictures and stories can provoke). The mind will naturally try and protect us from experiencing the continual horror and trauma to move us to a place which normalises this; which is as you also say, how the nation can become so desensitised to these images, stories, or events.

How do we cope? Well the above is one way to cope. To accept that this is normal in some places; that it exists, and that sometimes it is ‘out of sight out of mind’. Personally, I choose to see it and whilst it does become familiar I choose to balance the experience and do something with it. So, what is a personal cure? I wonder if it need be cured? Can we simply get over being fatigued from compassion if we are compassionate persons? I am not sure on the answer of that, but simply for me I need to refill the well.

It might sound oversimplified …. but I swim, I quieten my mind, I find and accept beauty in simple acts of humanity, in the landscape, I develop healthy relationships that balance me, that I am grateful for, I feel in good ways, I love, and I become grateful for the small things that I have no matter how insignificant they are and then I remember how lucky I am, and I address my thoughts and especially express the thoughts that contain words around others pain. Ultimately, I try and find peace and give a narrative to the feeling. Then I am able to fill the well back up and continue.

Compassion fatigue can be a crippling thing which can, if you let it, saturate your soul. I have often felt that it is important to think about how these things impact on us and as in some way leave indelible marks. So, I was really please to stumble across your blog this morning. These images and storied change our worldview is forever and in some ways you loose your naivety about the world, people and things. However, the good thing is that often it can lead us to action.

If compassion is to become something beyond self-indulgence then it needs to be followed through by ‘just’ action. Real compassion doesn’t stop at a warm sensation of ‘feeling good’ it triggers responsible action at whatever level the recipient is able. There’s always something you can do to mitigate suffering. In the case of the third world, in the long term, this has to be through the education of women to control family sizes – regardless of a male preference for unprotected sex. If you can’t adopt children – or go there to help – charities can, and governments can be pressed to target aid. I don’t know how Don McCullen came away from that poor boy. It must have been very hard. Something to haunt you all your life. At the very least he showed it to the world via his skill: photography.