I am in the midst of a long-term project to document instances when empathy has flowered on a mass scale and shifted the course of human history. While empathy has periodically collapsed on a collective scale – just think of colonialism in Latin America or the Holocaust – there have also been moments when it has emerged as a force for positive and radical social change. If we want to tackle today’s global crises – from wealth inequality and armed conflict to climate change and food insecurity – we need to learn from the past and understand how empathy can be harnessed as a powerful tool to shift human behaviour and ignite social action. And one of the most interesting places to look is the evacuation of British children in World War Two. Continue reading

I am in the midst of a long-term project to document instances when empathy has flowered on a mass scale and shifted the course of human history. While empathy has periodically collapsed on a collective scale – just think of colonialism in Latin America or the Holocaust – there have also been moments when it has emerged as a force for positive and radical social change. If we want to tackle today’s global crises – from wealth inequality and armed conflict to climate change and food insecurity – we need to learn from the past and understand how empathy can be harnessed as a powerful tool to shift human behaviour and ignite social action. And one of the most interesting places to look is the evacuation of British children in World War Two. Continue reading

Category: politics

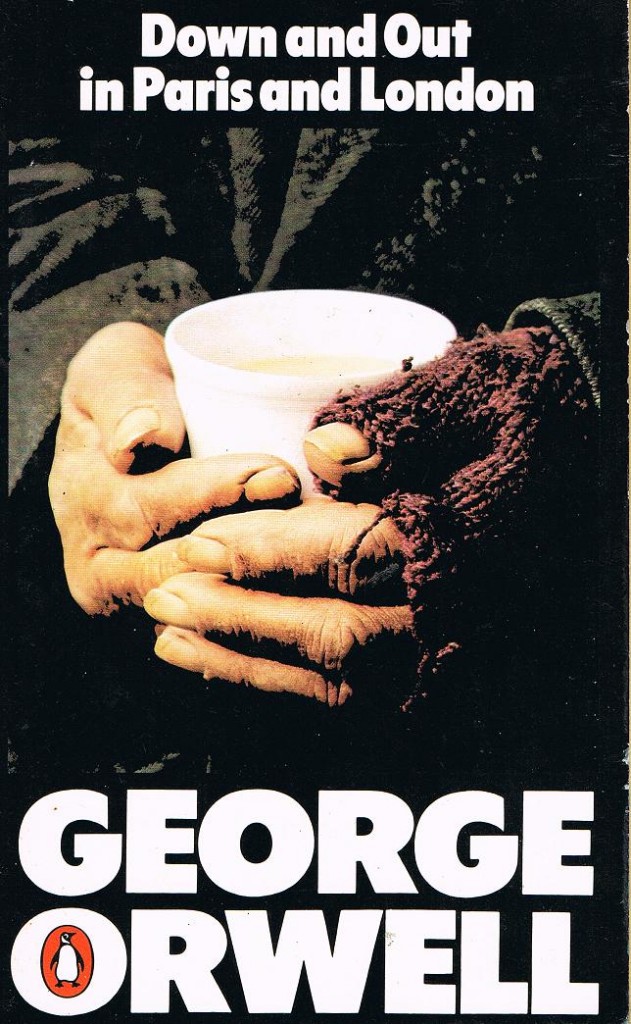

Why George Orwell is my empathy hero

I was recently interviewed by The Browser – a fabulous site which compiles quality writing from around the web – about my five top books on the art of living. In the following extract I discuss George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, a book which has been a major inspiration for all my work on empathy.

I was recently interviewed by The Browser – a fabulous site which compiles quality writing from around the web – about my five top books on the art of living. In the following extract I discuss George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, a book which has been a major inspiration for all my work on empathy.

George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London is your second choice. What does it teach us?

I think that Orwell was one of the great travel adventurers of the 20th century. The reason I think that is because in Down and Out in Paris and London he showed that empathy could become an extreme sport and the guideline for the art of living. It’s the second half of the book that I particularly like, in which he describes how he went tramping in east London. He would dress up as a tramp and go into the streets of London, fraternising with beggars and people living on the streets. He was trying to empathise with people who lived on the social margins. Continue reading

Five dead people to follow in 2012

Browse the self-help shelves of your local book store and you’ll spot that most titles draw on psychology, philosophy and religion for their wisdom. But there is one realm where few of them have sought inspiration: history.

When asking the big questions about life, love, work and death, we sometimes forget that people have been grappling with these issues for centuries – and that means we’re missing out. As Goethe put it, ‘he who cannot draw on three thousand years is living from hand to mouth’.

So how can characters from history help lead our lives in new directions in 2012? Here’s my personal selection of five icons from the past who offer good ideas for better living.

1.Matsuo Basho: make an alternative pilgrimage

The seventeenth-century Japanese poet Basho was a compulsive wanderer who reinvented the art of travel. On one of his pilgrimages, lasting over two years, he naturally visited the holiest Buddhist shrines. But his originality was also to make pilgrimages to non-religious sites that held deep personal meaning for him, such as seeking out the willow trees described by his favourite poets. Continue reading

The seventeenth-century Japanese poet Basho was a compulsive wanderer who reinvented the art of travel. On one of his pilgrimages, lasting over two years, he naturally visited the holiest Buddhist shrines. But his originality was also to make pilgrimages to non-religious sites that held deep personal meaning for him, such as seeking out the willow trees described by his favourite poets. Continue reading

How to be a Muslim, a Hindu, a Christian and a Jew

There is an intriguing thesis at the heart of Steven Pinker’s new book, The Better Angels of Our Nature. The Harvard psychologist argues – contrary to popular opinion – that humankind has become progressively less violent over the past few thousand years. We might feel surrounded by terrorism, civil wars and gun crime today, but murder and warfare is in fact on the decline. And the reason? One of Pinker’s key explanations is the rise of empathy as a force for social change: we are now more likely to look at the world through other people’s eyes, and consequently take action on their behalves. Continue reading

There is an intriguing thesis at the heart of Steven Pinker’s new book, The Better Angels of Our Nature. The Harvard psychologist argues – contrary to popular opinion – that humankind has become progressively less violent over the past few thousand years. We might feel surrounded by terrorism, civil wars and gun crime today, but murder and warfare is in fact on the decline. And the reason? One of Pinker’s key explanations is the rise of empathy as a force for social change: we are now more likely to look at the world through other people’s eyes, and consequently take action on their behalves. Continue reading

Empathy with the enemy

In the spring of 472 BC the people of Athens queued up to see the latest play written by Aeschylus, the founder of Greek tragedy. The Persians was an unusual production, and not only because it was based on an historical event rather than the usual legends of the gods. What must have really shocked the audience was that it was told through the eyes of their sworn enemy, the Persians, who only eight years earlier had fought the Athenians at the Battle of Salamis. Continue reading

In the spring of 472 BC the people of Athens queued up to see the latest play written by Aeschylus, the founder of Greek tragedy. The Persians was an unusual production, and not only because it was based on an historical event rather than the usual legends of the gods. What must have really shocked the audience was that it was told through the eyes of their sworn enemy, the Persians, who only eight years earlier had fought the Athenians at the Battle of Salamis. Continue reading

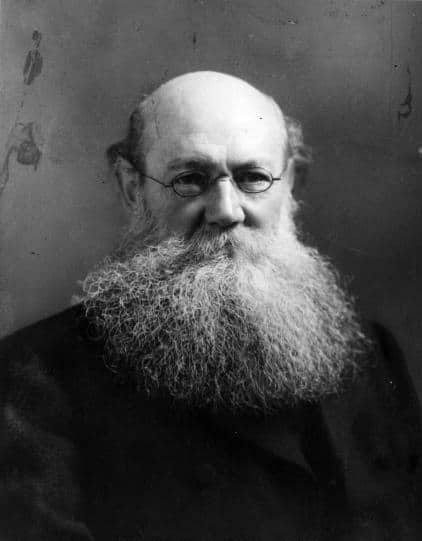

Podcast: Empathy, mutual aid and the anarchist prince

Download (right-click to save file) | Open Player in New Window

Peter Kropotkin was one of the greatest thinkers of the nineteenth century, who managed to multi-task as a Russian prince, renowned geographer and revolutionary anarchist. In this interview with Phonic FM, a wonderful community radio station based in Exeter, I discuss how Kropotkin’s ideas about ‘mutual aid’ relate to my own work on empathy, and why Kropotkin is a prophet for the art of living in the twenty-first century. The interview lasts around 50 minutes.Solstice Short Story Special: The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas

To celebrate the Winter Solstice – or Christmas if that is your festival of choice – I invite you to read one of the most moving pieces of empathic fiction ever written. It is a short story by Ursula Le Guin, ‘The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas’, first published in 1973. Le Guin says she based her psychomyth parable on an idea from the philosopher William James where he imagined a world in which millions of people could be kept permanently happy on the single condition ‘that a certain lost soul on the far-off edge of things should lead a life of lonely torment’. Here is the story in full. Continue reading

To celebrate the Winter Solstice – or Christmas if that is your festival of choice – I invite you to read one of the most moving pieces of empathic fiction ever written. It is a short story by Ursula Le Guin, ‘The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas’, first published in 1973. Le Guin says she based her psychomyth parable on an idea from the philosopher William James where he imagined a world in which millions of people could be kept permanently happy on the single condition ‘that a certain lost soul on the far-off edge of things should lead a life of lonely torment’. Here is the story in full. Continue reading

The day empathy saved the world

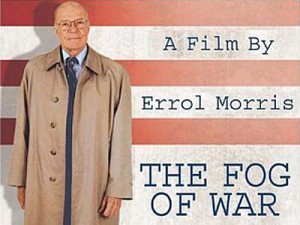

If you’ve ever sat up late wondering if empathy can save the world, I have good news for you. It can. Well, that is according to Robert McNamara, US Secretary of State from 1961 to 1968. In the Academy Award winning documentary The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara, the former bigwig in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations – who died last year aged 93 – reveals what he learned about war and foreign policy during his political career. The surprising first lesson is this: ’empathize with your enemy’.

McNamara makes his point through an account of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. He begins by describing the dilemmas faced by the Kennedy administration. Should they use military force to take out the Soviet nuclear weapons that would be pointing at 90 million Americans from Cuban soil? And if they attempted to do so, would the Russians press the nuclear button? One of Kennedy’s advisors was Tommy Thompson, a former US Ambassador to Moscow who knew Krushchev personally. He argued that Krushchev was unlikely to attack, and that they should hold back from military action. Thompson was recorded as saying at the time: ‘The important thing for Krushchev, it seems to me, is to be able to say, “I saved Cuba, I stopped invasion.”’ Luckily Kennedy followed Thompson’s advice and catastrophe was averted. This is McNamara’s comment on the episode:

In Thompson’s mind was this thought: Khrushchev’s gotten himself in a hell of a fix. He would then think to himself, ‘My God, if I can get out of this with a deal that I can say to the Russian people: “Kennedy was going to destroy Castro and I prevented it.”’ Thompson, knowing Khrushchev as he did, thought Khrushchev will accept that. And Thompson was right. That’s what I call empathy. We must try to put ourselves inside their skin and look at us through their eyes, just to understand the thoughts that lie behind their decisions and their actions.

Empathy, for McNamara, was a strategic weapon of the Cold War. It was one of their ways of beating the Russians. If you understand your enemy better than they understand you, then you are more likely to be victorious. Later in the film he laments that, ‘In the case of Vietnam, we didn’t know them well enough to empathize…we saw Vietnam as an element of the Cold War. Not what they saw it as: a civil war.’ That’s why the US failed.

The Cuban Missile Crisis can be seen as a moment when empathy saved the world. Without Tommy Thompson’s empathic imagination, Kennedy may have opted for military action and the Cold War could have turned into a very hot one. But it also raises questions about the meaning of empathy. Are we willing to tolerate an approach to empathy that permits it to become a strategic weapon of war?

McNamara is really talking about a cynical and self-serving form of empathy that I call ‘instrumental empathy’, which is used to promote personal interests. It is certainly not monopilised by politicians. Crafty casino owners use instrumental empathy to enter the mindset of gambling addicts and design slot machines that will fleece them of their cash. Psychopaths may make a similar mental leap into the minds of their victims in order to manipulate their fears.

McNamara gives empathy a bad name. Instead of using it as an instrument of personal gain, we should promote a more benign approach to empathy that expands, rather than diminishes, our humanity.

In case you a curious, here is the extraordinarily powerful clip on the Cuban Missile Crisis from The Fog of War. As well as music from Philip Glass, it contains original recordings of the discussions that took place between Kennedy, McNamara, Thompson and other top White House aides during the tense days of October 1962:

Global Map of the Empathic Imagination

Imagine you had to invent a new kind of atlas which showed the extent of our planet’s economic and cultural globalization, and the interconnections between the world’s environmental crises. That’s the aim of the ATLAS of Interdependence, a project being masterminded by the new economics foundation, the Open University and Sheffield University. The ATLAS will be an evolving online resource containing entries from geologists, geographers, scientists, journalists, artists, campaigners and historians, each providing their personal vision of global interdependence. Here is a sneak preview of my own entry, called the Global Map of the Empathic Imagination. Do let me know if you think it needs any additional landmarks. Continue reading

Imagine you had to invent a new kind of atlas which showed the extent of our planet’s economic and cultural globalization, and the interconnections between the world’s environmental crises. That’s the aim of the ATLAS of Interdependence, a project being masterminded by the new economics foundation, the Open University and Sheffield University. The ATLAS will be an evolving online resource containing entries from geologists, geographers, scientists, journalists, artists, campaigners and historians, each providing their personal vision of global interdependence. Here is a sneak preview of my own entry, called the Global Map of the Empathic Imagination. Do let me know if you think it needs any additional landmarks. Continue reading

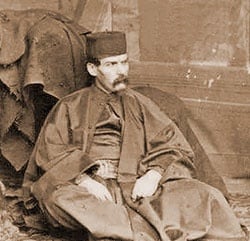

Who was the greatest Victorian traveller? A fish collector

Who was the greatest traveller of the Victorian era? Amongst the usual top contenders you will find the name of Sir Richard Francis Burton. Best known for translating The Thousand and One Nights from Arabic and for visiting Mecca in 1853 disguised as a Muslim pilgrim, Burton wandered for years throughout the Middle East, Far East and Africa. He had an extraordinary talent for languages – he could speak twenty-nine of them – and was a master of assimilating himself into local cultures. Just after his death in 1890 he was described as ‘a Mohammedan among Mohammedans, a Mormon among Mormons, a Sufi among the Shazlis, and a Catholic among the Catholics.’ Continue reading