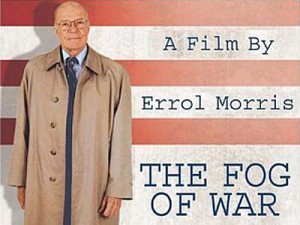

If you’ve ever sat up late wondering if empathy can save the world, I have good news for you. It can. Well, that is according to Robert McNamara, US Secretary of State from 1961 to 1968. In the Academy Award winning documentary The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara, the former bigwig in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations – who died last year aged 93 – reveals what he learned about war and foreign policy during his political career. The surprising first lesson is this: ’empathize with your enemy’.

McNamara makes his point through an account of the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. He begins by describing the dilemmas faced by the Kennedy administration. Should they use military force to take out the Soviet nuclear weapons that would be pointing at 90 million Americans from Cuban soil? And if they attempted to do so, would the Russians press the nuclear button? One of Kennedy’s advisors was Tommy Thompson, a former US Ambassador to Moscow who knew Krushchev personally. He argued that Krushchev was unlikely to attack, and that they should hold back from military action. Thompson was recorded as saying at the time: ‘The important thing for Krushchev, it seems to me, is to be able to say, “I saved Cuba, I stopped invasion.”’ Luckily Kennedy followed Thompson’s advice and catastrophe was averted. This is McNamara’s comment on the episode:

In Thompson’s mind was this thought: Khrushchev’s gotten himself in a hell of a fix. He would then think to himself, ‘My God, if I can get out of this with a deal that I can say to the Russian people: “Kennedy was going to destroy Castro and I prevented it.”’ Thompson, knowing Khrushchev as he did, thought Khrushchev will accept that. And Thompson was right. That’s what I call empathy. We must try to put ourselves inside their skin and look at us through their eyes, just to understand the thoughts that lie behind their decisions and their actions.

Empathy, for McNamara, was a strategic weapon of the Cold War. It was one of their ways of beating the Russians. If you understand your enemy better than they understand you, then you are more likely to be victorious. Later in the film he laments that, ‘In the case of Vietnam, we didn’t know them well enough to empathize…we saw Vietnam as an element of the Cold War. Not what they saw it as: a civil war.’ That’s why the US failed.

The Cuban Missile Crisis can be seen as a moment when empathy saved the world. Without Tommy Thompson’s empathic imagination, Kennedy may have opted for military action and the Cold War could have turned into a very hot one. But it also raises questions about the meaning of empathy. Are we willing to tolerate an approach to empathy that permits it to become a strategic weapon of war?

McNamara is really talking about a cynical and self-serving form of empathy that I call ‘instrumental empathy’, which is used to promote personal interests. It is certainly not monopilised by politicians. Crafty casino owners use instrumental empathy to enter the mindset of gambling addicts and design slot machines that will fleece them of their cash. Psychopaths may make a similar mental leap into the minds of their victims in order to manipulate their fears.

McNamara gives empathy a bad name. Instead of using it as an instrument of personal gain, we should promote a more benign approach to empathy that expands, rather than diminishes, our humanity.

In case you a curious, here is the extraordinarily powerful clip on the Cuban Missile Crisis from The Fog of War. As well as music from Philip Glass, it contains original recordings of the discussions that took place between Kennedy, McNamara, Thompson and other top White House aides during the tense days of October 1962:

If we accept that we a warlike species, which history demonstrates to be the case, then empathy is needed to prevent a state of perpetual war, whether it be to win the hearts and minds of the enemy, or to understand when a conflict is unwinnable where invaders are seen as occupiers as opposed to liberators.