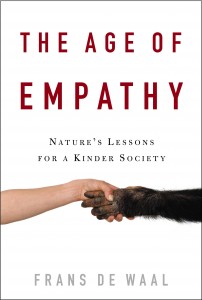

In an exclusive interview for OUTROSPECTION, I speak to the renowned Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal about his new book, The Age of Empathy: Nature’s Lessons for a Kinder Society. De Waal, voted by Time Magazine as one of the 100 World’s Most Influential People Today, is Professor of Primate Behaviour at Emory University in the US. Author of numerous books on social cooperation in primates, he is famous for arguing that empathy is a natural trait in humans and many animal species.

In an exclusive interview for OUTROSPECTION, I speak to the renowned Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal about his new book, The Age of Empathy: Nature’s Lessons for a Kinder Society. De Waal, voted by Time Magazine as one of the 100 World’s Most Influential People Today, is Professor of Primate Behaviour at Emory University in the US. Author of numerous books on social cooperation in primates, he is famous for arguing that empathy is a natural trait in humans and many animal species.

Roman Krznaric: What is the central argument of your new book, The Age of Empathy, and why do you think empathy is such an important idea in today’s world?

Frans de Waal: The evolution of empathy has been an interest of mine since my 1996 book Good Natured. Since then, so many studies have been conducted both by others and by my own team on human and animal empathy that it is getting hard to keep up. The field is blooming, especially in human neuroscience, but increasingly also with regard to animals. There are now empathy studies on mice, monkeys, apes, elephants, et cetera. Since the general public knows little about these developments, they beg to be summarized, which is what I have set out to do in this book, exploring the origins of empathy through all disciplines, from human psychology to animal behavior, and from brain imaging to the evolution of sociality.

My second reason is a bit more political. I can’t stand the many references to biology by conservatives in this country, especially by those who do not really believe in evolution. They use biology as a convenient justification for their policies, saying that since nature is based on a “struggle for life” we ought to build our societies around selfishness and competition. They read into nature what they want to, and I feel it is my task to point out that they got it all wrong. There are many animals that survive through cooperation, and our own species in particular comes from a long line of ancestors dependent on each other. Empathy and solidarity are bred into us, so that our society’s design ought to reflect this side of the human species, too. I have nothing against a market economy, but there is more to life than making money.

My sensitivity in this regard goes back to the early debates, in the 1960s and 70s, about the aggressive instinct. No one denies that humans are aggressive – in fact, I consider us one of the most aggressive primates – yet the recent discovery of the Ardipithecus fossil should make everyone who believes we are born “killer apes” think twice. Ardipithecus is believed to be close to the split between humans and apes, yet was probably less aggressive than the current chimpanzee. Perhaps Ardipithecus was more like our other close relative, the bonobo. All of the nonsense we have been fed about being inherently aggressive and being predestined to wage war is open to question if in fact we descend from a peaceful, hippie-like bonobo.

Roman Krznaric: What is the single best piece of evidence you have come across showing that empathy – both in animals and humans – is a natural trait that has emerged as part of our evolutionary development?

We have collected thousands of observations of so-called consolation behavior in chimpanzees. As soon as one among them is distressed (has lost a fight, dropped out of a tree, encounters a snake) others will come over to provide reassurance. They embrace the distressed chimp or try to calm him or her with a kiss and grooming. This behavior is typical of chimps (and other apes), and is used in research on children as the main behavioral marker of “sympathetic concern”. I am a Darwinist and follow the assumption that if two closely related species show similar behavior under similar circumstances the psychology behind it is probably similar, too. This is the most parsimonious position, and means of course that if such behavior rests on empathy in the human child it does so, too, in the ape. In fact recent studies support the idea that consolation reduces stress in the recipient.

Experimental evidence is harder to collect but studies are beginning to do so. We conducted recently an experiment on spontaneous altruistic behavior, which in humans is usually explained as a product of empathy. In one experiment, we placed two capuchin monkeys side by side: separate, but in full view. One of them needed to barter with us with small plastic tokens. The critical test came when we offered a choice between two differently colored tokens with different meaning: one token was “selfish”, the other “prosocial”. If the bartering monkey picked the selfish token, it received a small piece of apple for returning it, but its partner got nothing. The prosocial token, on the other hand, rewarded both monkeys equally at the same time. The monkeys gradually began to prefer the prosocial token. The procedures were repeated many times with different pairs of monkeys and different sets of tokens, and the monkeys kept picking the prosocial option showing how much they care about each other’s welfare. This was not based on fear for possible repercussions, because we found that the most dominant monkeys (who have least to fear) were in fact the most generous.

Roman Krznaric: You have sometimes been accused of ‘overinterpreting’ the evidence. For instance, you have cited the example of a gorilla called Binti, who, when a three-year-old boy fell into her cage in the zoo, picked him up, comforted him, then carried him to a door where the zookeepers could remove him. You have argued that this is an instance of empathy. But critics have suggested it could well be evidence of some other trait, such as sympathy or pity. How do you respond?

Frans de Waal: Is this truly an alternative? Does anyone believe sympathy can be achieved without empathy? Empathy is the process of emotional resonance and perspective-taking that we use to be in tune with and understand others. How could one develop sympathy without it? For sympathy to be discriminating it needs to be based on what we think is happening with the other, which is based on empathy. For me all of these phenomena are continuous, from emotional contagion to concern for others to helping actions. It is all related.

But let’s face it, the case of Binti the gorilla cannot prove any of this. I use it as an illustration, just as I use many other illustrations, but the real work needs to be done through systematic research, either by observing hundreds of helping actions among primates (as has been done by several research teams) or by conducting experiments, in which we manipulate a situation in order to see how animals respond. Under the previous question I described such an experiment, and there are many others that have been published in the last few years.

The problem with experiments, though, is that they never concern very risky behavior. In the jargon of my field, they invariably concern “low-cost altruism”. No one is going to throw a human child in with the gorillas to see how they respond, and no one is going to push a baby elephant into a mud hole to see how the adults will save it. For this reason, we have no systematic evidence on animal risky helping behavior just as we don’t have such evidence for humans. We know that humans rescue others who are drowning or asleep in a burning building, but this is all anecdotal material similar the material that we have for animals. Anyone who criticizes the Binti story should keep in mind that we then also should discard all those cases of human heroism. It’s all anecdotal.

Roman Krznaric: As individual human beings, what can we do to develop our natural capacity to empathize?

Frans de Waal: It is instructive to see how political leaders have historically promoted the opposite of empathy (i.e. hatred). The process is called “dehumanization”: emphasize differences by depicting an entire group of people as “rats” or “cockroaches”, saying they are not human, thus making clear how much they differ from us. Hitler did this with the Jews.

Empathy is promoted by similarity and social closeness. Studies have shown this to be true for mice, for monkeys and for humans. The way to promote empathy is the opposite of dehumanization, so we could call it “humanization” because it emphasizes how similar others are to us. We stress that they look the same, feel the same, share the same interests. This helps us empathize.

Find out more about Frans de Waal’s ideas on empathy and the secrets of our evolutionary empathetic inheritance by treating yourself to his fabulous new book.

2 thoughts on “In search of our inner ape: An interview with Frans de Waal”