After being out of print for nearly a century, Helen Keller’s sensational collection of essays, The World I Live In, has recently reappeared in a variety of editions. Although her life is often remembered as an uplifting tale of personal triumph over extreme physical adversity, it is just as much an inspiration for how to expand our imaginations. By taking us on a journey into her dark and soundless world, her writings can help us rethink the nature of perception itself.

After being out of print for nearly a century, Helen Keller’s sensational collection of essays, The World I Live In, has recently reappeared in a variety of editions. Although her life is often remembered as an uplifting tale of personal triumph over extreme physical adversity, it is just as much an inspiration for how to expand our imaginations. By taking us on a journey into her dark and soundless world, her writings can help us rethink the nature of perception itself.

Born into a prosperous family in northern Alabama in 1880, Helen had a normal childhood until the age of nineteenth months, when she suffered from a terrible illness – probably meningitis – which left her deaf and blind. Over the following years she developed into a headstrong, even aggressive child. She would lock unsuspecting family members in their rooms and then hide the key, and throw violent tantrums when she didn’t get her way or was frustrated at an inability to express herself. But when Helen was seven years old, her life changed utterly. Her father sought the advice of Dr Alexander Graham Bell – not only the inventor of the telephone but a renowned expert in deafness – who suggested employing a teacher from the Perkins Institution for the Blind in Boston. A few months later, Anne Mansfield Sullivan arrived to live with the family in Alabama.

Annie’s method of teaching Helen to communicate was to ‘speak’ into her hand, using a language of hand signs which represented letters of the alphabet, a kind of fingered Morse code. At first Helen was unable to make any connection when the word d-o-l-l was spelled into one hand as she held her doll in the other. But there soon occurred one of the most life-changing moments in the history of the human imagination, when Annie placed her pupil’s hand under a spout of water. As Helen recorded in her autobiography:

As the cool stream gushed over one hand she spelled into the other the word water, first slowly, then rapidly. I stood still, my whole attention fixed upon the motions of her fingers. Suddenly I felt a misty consciousness as of something forgotten – a thrill of returning thought; and somehow the mystery of language was revealed to me. I knew then that ‘w-a-t-e-r’ meant the wonderful cool something that was flowing over my hand. The living world awakened in my soul, gave it light, hope, joy, set it free!

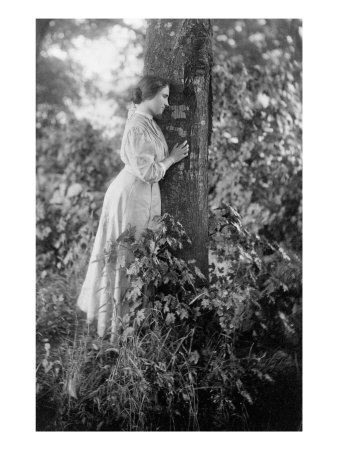

Helen had learned that everything had a name, and that the manual alphabet was the key to knowledge. ‘As we returned to the house every object which I touched seemed to quiver with life.’ Within a few hours she had added thirty more words to her vocabulary. Soon she was reading Braille, and only three months after the water revelation, Helen wrote her first letter. Although shrouded in darkness and silence, Helen’s intellect flowered. In 1900 she entered Radcliffe College, and four years later was the first deaf-blind person ever to graduate from an institution of higher learning. Following university, Helen established herself as a writer and lecturer, a passionate advocate for the deaf and blind, and a socialist activist. Her fame spread and she was photographed meeting the great and the good of her age – from Mark Twain to President Kennedy – usually with Annie Sullivan translating into her hand by her side. Her autobiography, The Story of My Life, sold millions, and was made into the 1962 Oscar-winning film, The Miracle Worker.

Helen’s sensory abilities were unbelievably sharp and sophisticated, and she was able to express her perceptual experiences with a poetic beauty. In her essay collection The World I Live In, Helen described how she possessed what she called ‘a seeing hand’:

Ideas make the world we live in, and impressions furnish ideas. My world is built of touch-sensations, devoid of physical colour and sound; but without colour and sound it breathes and throbs with life…The coolness of a water-lily rounding into bloom is different from the coolness of an evening wind in summer, and different again from the coolness of the rain that soaks into the hearts of growing things and gives them life and body. The velvet of the rose is not that of a ripe peach or of a baby’s dimpled cheek. The hardness of the rock is to the hardness of wood what a man’s deep bass is to a woman’s voice when it is low. What I call beauty I find in certain combinations of all these qualities, and is largely derived from the flow of curved and straight lines which is over all things…Remember that you, dependent on your sight, do not realize how many things are tangible.

Helen listened to classical music through the vibrations and could tell the age and sex of strangers through the resonance of their walk on the floorboards. One day, when wandering through a favourite wood, she felt an unexpected rush of air coming from one side, and knew that nearby trees she loved must have recently been felled. She could recognise all her friends instantly by their individual odours. She even claimed to comprehend colour through the power of analogy: ‘I understand how scarlet can differ from crimson because I know that the smell of an orange is not the smell of a grape-fruit.’ Yet she recognised the limits on her knowledge, for she could never sense a room or a sculpture in its entirety, and was always piecing together the small portions of the world her fingers could touch at any one moment.

What is Helen Keller’s message for the art of living? ‘I have walked with people whose eyes are full of light, but who see nothing in wood, sea, or sky, nothing in city streets, nothing in books. What a witless masquerade is this seeing!…When they look at things, they put their hands in their pockets. No doubt that is one reason why their knowledge is often so vague, inaccurate, and useless.’ Our task, it seems, is to take our hands out of our pockets, and cultivate not just our sense of touch, but all our senses. That is how we might both deepen our experiences of life and, ultimately, nourish our minds. ‘We differ, blind and seeing, one from another, not in our senses, but in the use we make of them, in the imagination and courage with which we seek wisdom beyond our senses.’

For a small taste of The Miracle Worker, have a look at the classic breakfast scene, in which Annie Sullivan (Anne Bancroft) attempts to get her new unruly pupil Helen (Patty Duke) under control: