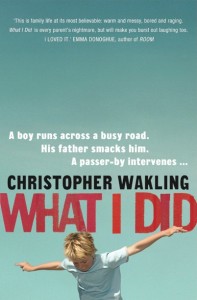

Christopher Wakling’s new novel, What I Did, is a brilliant, dark and often excruciatingly funny journey into a family nightmare. Narrated by a six-year-old boy obsessed with the animal kingdom, it has been the recipient of scintillating reviews, was nominated for the Booker Prize and is fast becoming a book club favourite. I talked to the author – who is also a respected teacher of creative writing – about what it takes to write through a child’s eyes, and what can happen to you when you do.

Christopher Wakling’s new novel, What I Did, is a brilliant, dark and often excruciatingly funny journey into a family nightmare. Narrated by a six-year-old boy obsessed with the animal kingdom, it has been the recipient of scintillating reviews, was nominated for the Booker Prize and is fast becoming a book club favourite. I talked to the author – who is also a respected teacher of creative writing – about what it takes to write through a child’s eyes, and what can happen to you when you do.

Roman Krznaric: To what extent is What I Did a new direction for you as a novelist?

Christopher Wakling: Each of my novels has felt like a step away from the one before it, but with What I Did I took a leap.

That’s largely to do with the narrative voice. Billy is six, and he tells the story. It begins when he runs away from his father and into a busy road. Billy’s father catches him up and smacks him, hard. When a passer-by objects, Billy’s dad tells her to get lost.

She does the opposite. She informs social services, who launch an investigation into the family, an investigation with which Billy’s dad refuses to cooperate, and the implications of which Billy cannot understand. Between them they make matters infinitely worse…

So on one level the book is about the boundary between the state and the family and the issue of whether or not it’s ever justifiable to smack a child. But it’s also about parental love – how far will we go to protect and hang on to those we love?

And at its core, because of its narrative voice, the novel is about childhood, about being six: the extreme present-tenseness; the jump-cuts in focus; and the frequently hilarious misunderstandings children make.

Although the subject matter is dark, Billy’s voice leavens the novel, I hope.

Roman Krznaric: How did you go about discovering what it’s like to be inside the mind of a six-year-old boy? And what were the biggest surprises and challenges along the way?

Christopher Wakling: I had a cunning master-plan. It involved getting my wife pregnant, and lying in wait for about six years.

No, I can’t claim that. But I do have two small children, and I have been lucky enough to spend a great deal of time looking after them through and beyond their pre-school years.

By ‘lucky enough’ I mean completely in love, and ‘murderously bored’ for long stretches.

Until, that was, I made myself focus hard on what was in front of me. What were my children thinking? What did they get, and what didn’t they understand?

It’s a common misconception that children say exactly what they mean. They don’t: though they’re often pretty transparent, there’s a subtext to child-speak, too.

I started writing down the things they said. I filled notebooks with observations and transcriptions of conversations. Then I started stringing bits of notebook together.

This didn’t equate to a voice, as such; as with any narrative standpoint, creating Billy’s voice meant shaping and altering real life. Stealing, then lying. The stealing bit takes patience and a willingness to try and see the world through another pair of eyes. The lying bit is a lot of fun.

Roman Krznaric: Do you think a novel can work if the writer doesn’t make the reader empathise with the main characters?

Christopher Wakling: No. I don’t think the reader has to like the main characters (though book-groups up and down the land are testimony to the fact that it helps if they do), but in order to believe in a fictional protagonist readers certainly have to understand where that character is coming from. What does the character want? Where did they begin? Where are they trying to go? These questions establish motive and are useful for the plot. But the bigger question – how does the character see the world? – has the power, if answered convincingly by a novelist, to immerse the reader in a new consciousness. Do that well and readers will care about the world of the novel beyond the last page.

Roman Krznaric: In what ways did writing What I Did change the way you look at yourself, and at society?

Christopher Wakling: Writing – and researching – the novel made me more aware of the impossibly hard job undertaken by child protection workers.

They can’t win: they’re damned if they fail to intervene where a child is suffering abuse, and they’re damned if they step in where there is no need.

High profile ‘Baby P’ cases illustrate the former difficulty; there are fewer stories (partly a result of the secrecy cloaking the family courts) illustrating the latter.

I did, however, read a number of articles by Camilla Cavendish in the Times a few years ago, cataloguing families torn apart by accusations which later proved to be unfounded.

These made me think: what would I do faced with a situation in which somebody was trying to take my children away, saying it was for their own benefit. I hope I wouldn’t be as unreasonable as Jim (Billy’s father in the book) but I don’t know.

And writing about whether it is ever justifiable to smack a child made me reassess our society’s moral code, as well as my own. When I was growing up, smacking was the norm. Now it’s not. This change interested me. The book doesn’t preach on the subject, but it explores the ramifications of the shift.

Roman Krznaric: Your novel has been compared to Emma Donoghue’s Room, which is narrated by a five-year-old boy. How would you personally describe the literary tradition to which What I Did belongs?

Christopher Wakling: What I Did taps into a rich seam of books narrated by children. Novels such as The Catcher in the Rye, Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night Time, A Clockwork Orange, Vernon God Little, The Butcher Boy, and – most recently – Room, of course. (Ironically, Room is the only one I hadn’t read before I wrote the novel: it hadn’t come out yet.)

First person stories tend to be more immediate, skewed, and potentially disorientating than most; childhood is all of these things, times ten. These books are therefore an extreme form of first person narrative.

The gap between what the narrator thinks is going on and what the reader knows is actually the case is often wider with a child narrator. The younger the child, the wider it gets. The disjunct can be poignant, telling and hilarious by turns. It’s a challenge for a writer to control, but it’s also rewarding…

Roman Krznaric: I am constructing a library of the greatest Empathy Books of all time – books which allow us to step into the shoes of others and create a human connection. What five books would you like to put in my library?

Christopher Wakling: The child’s perspective should be represented in this library of yours, so I’ll go for any five of the books mentioned above. Take your pick. But make sure you include The Butcher Boy. And The Catcher in the Rye, and A Clockwork Orange. And two more. One of which should be mine…

One thought on “To smack or not to smack? An interview with Christopher Wakling”