I was recently interviewed by philosopher Jules Evans, author of the bestselling Philosophy for Life: And Other Dangerous Situations, as part of his project on the rise of the practical philosophy movement. The interview originally appeared on his website. Here it is in full.

I was recently interviewed by philosopher Jules Evans, author of the bestselling Philosophy for Life: And Other Dangerous Situations, as part of his project on the rise of the practical philosophy movement. The interview originally appeared on his website. Here it is in full.

Roman Krznaric is the author of two popular books that came out this year – The Wonderbox: Curious histories of how to live and How to Find Fulfilling Work – and is also one of the founding faculty members of The School of Life, which teaches the art of living to its clientele. He talked to me about his work in the past with Theodore Zeldin, how The School of Life came to be, and how the practical philosophy movement can do more than offer lifestyle tips, and might even help to tackle the great problems of the age.

Would you say there is such a thing as a ‘practical philosophy movement’?

Yes, though it’s a very broad movement. What’s happened is that over the last 20 years there’s been a revolutionary rise of interest in the question of how to live. And that question has taken a practical focus in many ways, through philosophy clubs and organisations like the School of Life and Oxford Muse.

Why is there this interest in the question of how to live? Why now?

A number of factors spring to mind. Firstly, in the last decade or two, there’s been a flux or crisis in the art of living because of rapid technological changes, like the growth of online dating and social networks, which are raising new issues about how we conduct our relationships. Questions about how to live have also arisen because of the perceived failure of consumerism to deliver the good life, and due to advances in medical technology which mean we’re living longer than ever and having to think more about how to spend the extra years granted to us. Another factor is that people are rethinking their lifestyle choices in the face of the growing threat of climate change.

And finally, I’d suggest these questions have become more prominent as an unintended consequence of the Freudian revolution. We’ve just emerged from a century of psychoanalysis, of a therapy culture that says look inside of yourselves. That inner gaze has not done enough to solve the dilemmas of life. So we’re beginning to look outside of professional therapy for answers, and we’re looking to more communal places like The School of Life or the London Philosophy Club.

A lot of those questions about the good life, it seems to me, were asked by student radicals in the 1960s. One of my hypotheses is that the practical philosophy movement is in some ways the child of 1968.

Perhaps. Though of course the 1970s was the Me Decade, when self-obsession reached new heights. It’s reflected in the rise of things like erhard seminars training, Maharishi communes, therapy culture. Peter Singer writes about this in How Are We to Live?: Ethics in an Age of Self-Interest (1997), where he notes that all his academic colleagues are on therapy, spending a quarter of their salary on analysis. He thought they were being too inward looking in their search for the good life.

So do you think self-help is just selfish and narcissistic?

There are competing streams in the broad self-help movement. In the 1970s and 1980s, you see a very commercial version of self-help emerge, which is all about scrambling up the corporate ladder. Then, as a counter to that, you have a more spiritual form of self help, people like Ram Dass, and the simple living movement which arose in the 1980s. The dominant stream, however, was the commercial / corporate form of self-help.

Tell me how you got into this area.

When I was 17, I discovered Bertrand Russell and read his books. Then, from 1989 to 1992, I studied Politics, Philosophy and Economics at Oxford. I discovered to my horror that the great questions of how to live were not addressed in an Oxford PPE degree. This was a great disappointment. I’m not certain that academic philosophy has changed much since then. Academic philosophy has mainly failed to respond to the public demand for guidance as to how to live, and has lost the Ancient Greek ideal that philosophy is something that should be applied to the dilemmas of everyday living.

After graduating from Oxford, I travelled for a couple of years, then I did a masters in Latin American Studies. Following that I did a PhD in political sociology, and began university teaching, mainly in the fields of sociology and politics. I didn’t at that point have any intention to be a philosopher, or write popular philosophy books (in fact, I don’t really think of myself as a philosopher). But I came to believe that the best way to achieve social and political change was not through big structural changes such as new laws or institutions, but rather that the biggest changes in history came through changes in individual relations, through the flowering of empathy. I became very interested in empathy, as a meeting point between the art of living and social change. And that led me to leave academia, because at that point empathy couldn’t easily be researched in academia. It was seen as a psychological phenomenon, and I saw it as more complicated and as involving many different disciplines. I also wanted my investigation to be more practical and to affect people’s lives.

So you left academia. It strikes me that many interesting intellectuals of your age left academia – Alain de Botton, Adam Curtis, George Monbiot. Why the diaspora?

By the late 1990s, to be an intellectual and thinker, you had to escape from the bureaucracy of academia. Take George Monbiot. He could easily be a professor in a range of academic fields – he has enormous scholarly acumen – but my sense is that he feels more intellectual freedom outside of academia, and has more space to pursue his political activism (he has, though, been a visiting professor at several universities). I feel that The Wonderbox is no less rigorous than an academic work. But academics have always been suspicious of popularising or outreach, particularly in history. Historians are embarrassed to look into the past and find lessons for today. Or they think history can teach us how to organize big political systems, not so much provide life lessons on the individual level.

So what options were there for thinkers outside of academia in the late 1990s?

By a fluke, my partner, a development economist, had a research assistant who was working with Theodore Zeldin. I’d read Zeldin’s An Intimate History Of Humanity, and thought it was one of the greatest books I’d read. I’d heard a talk by him about conversations on the radio. Then I discovered that Zeldin had an organisation in Oxford, where I lived, called The Oxford Muse. I went to meet him one evening, at a dinner organized by my partner’s research assistant. He liked me, I liked him, and I was intrigued by what The Oxford Muse was trying to do – create conversations that promoted mutual empathy.

What is Zeldin like?

I thought he was one of the most amazing and original thinkers I’d met. I worked with him for three and a half years, and what I really noticed was how he would question absolutely everything. He would come into The Oxford Muse and say ‘right, today we’re going to re-invent the insurance industry’, or he’d say ‘there’s a problem with money, we need an alternative’. Then he’d spend months trying to come up with an alternative. He incorporated his daily experience into his ideas, and he never described The Oxford Muse the same way twice. My time working with him was enormously intellectually invigorating.

Tell me about his Feast of Strangers project.

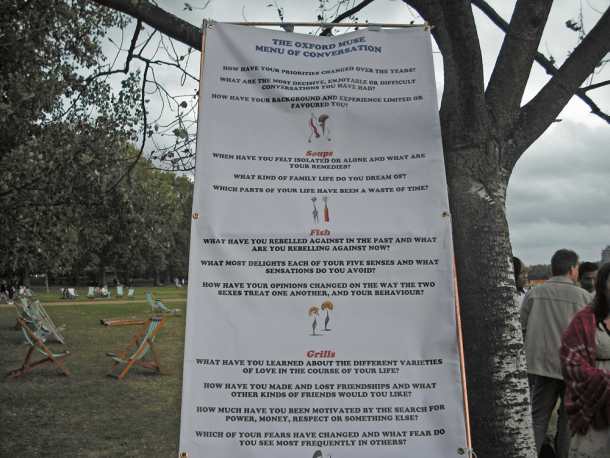

They’re basically what The Oxford Muse calls Conversation Meals, using a Menu of Conversation containing questions like ‘What have you learned about the different varieties of love in the course of your life?’. It’s very philosophical – you try to get strangers to talk about how they see the world and themselves. We would try to draw together different groups, like CEOs and homeless people. Or, within companies, we would create conversations across hierarchies. Zeldin thinks that, in a conversation between two people, it is possible to create a tiny bit of understanding and equality – that’s how you change the world, using a microcosmic strategy, one conversation at a time. Another thing we did at The Oxford Muse was to create written portraits of people around Oxford, where they describe themselves and their philosophy of life in their own words. We recruited hundreds of volunteers to talk to people, and created a book called Guide to An Unknown University – revealing the lives of people from every walk of life who exist around Oxford.

So you left The Oxford Muse in 2006.

Yes, I felt it was time to move on. I wanted to teach my own courses on the art of living, so started to do that.

Where?

Well, in the beginning I couldn’t find a venue, so the first courses were held in my kitchen. I covered topics such as love, time, work and empathy, and particularly approached them through the lens of cultural history. How can looking at the past help us rethink our approach to everyday life? I also wanted to encourage creative and adventurous thinking about how to live. Gradually, those classes shifted into the public realm. The QI Club in Oxford was looking for new public events, so I began running evening workshops there. My first one was on Love and the Art of Living. I tried to make them as participatory as possible, to get away from the academic seminar format. My main advice is never to speak for more than 20 minutes before you give the audience an opportunity to participate. Try to make ideas accessible and get the audience to work on them. For example, if I was teaching a course on love, I’d not only speak about the history and philosophy of love, I’d get people to draw ‘love maps’ depicting the different kinds of love in their own lives. I thought hard about teaching and the structure of workshops.

To what extent did you feel you were doing something new and unusual?

I didn’t know anybody else doing those sort of classes. I knew of the School of Economic Science’s courses in practical philosophy, but that’s different [Jules’ note: they’re a neo-platonic sect, as I describe in my book]. Then, in 2007, Alain de Botton, who knew about my work at The Oxford Muse, got in touch to talk about the possibility of setting up some kind of ‘university of life’. This is what eventually became The School of Life. Its first director, Sophie Howarth, was the driving force behind shaping the intellectual approach and feel. She asked me to develop one of the five core courses that The School of Life was going to offer, on the topic of work. The love course was developed mainly by Mark Vernon and Alain, the family course by Charles Ferneyhough and Rebecca Abrams, politics by Maurice Glasman and myself, and play I believe grew out of Sophie Howarth’s ideas. Other thinkers such as the philosopher Robert Rowland Smith were also involved. They were all designed to be six week courses, or intensive weekend courses.

Preparing the launch of the School in 2007 and 2008 was a very wonderful period of my life. I wrote a 100,000 word course handbook for the work course, drawing on literature, philosophy, history, anthropology. People don’t realise how much intellectual work went into the School of Life. We’d all draft sections of courses, then come together to discuss them, try out classes, hammer out ideas. It was done very professionally, and required a lot of hard work to get right. We were trying to do something that had never been done: to create a university of life, which was an alternative to mainstream university, intellectually vibrant and absolutely practical.

Preparing the launch of the School in 2007 and 2008 was a very wonderful period of my life. I wrote a 100,000 word course handbook for the work course, drawing on literature, philosophy, history, anthropology. People don’t realise how much intellectual work went into the School of Life. We’d all draft sections of courses, then come together to discuss them, try out classes, hammer out ideas. It was done very professionally, and required a lot of hard work to get right. We were trying to do something that had never been done: to create a university of life, which was an alternative to mainstream university, intellectually vibrant and absolutely practical.

Most of the people that Sophie Howarth recruited and that Alain got onboard were trying to develop their ideas and careers outside of academia. But they were all academically very well qualified: Robert Rowland Smith had been a fellow of All Souls, Mark Vernon was a PhD, Maurice Glasman was a lecturer at London Met, Rebecca Abrams had published books on family relations (while also teaching creative writing at Oxford University), and Alain got a double starred first in history at Cambridge.

How was it funded?

The idea was that funds were available to get it going for the first few years. There were debates about pricing, and about balancing financial sustainability with accessibility. We felt the courses were affordable – a lot cheaper than the cost of doing an Open University degree, for example. We had to charge, though, to make the School self-sustaining. We also wanted it to expand – the idea was always not just to have one School of Life, but one on every high street.

Was it Sophie’s plan at the beginning to make it more of a social enterprise?

Well, Sophie came from the Tate Musuems’ public engagement programme. Her idea was that The School of Life should strive to be as community-orientated as possible. Although not set up as a charitable foundation, it was certainly not intended that it should be a great profit-making enterprise. Sophie eventually left to start a family, rather than because of any disagreements. The School of Life is now very lucky to have Morgwn Rimel as the director, who is doing a great job taking it forward.

How has the School done?

It’s now almost four years since it launched. It’s been amazingly successful. Approximately 50,000 people have come through its doors. It is clear that there is a real hunger for public spaces where people can think about the big questions of everyday life.

Has it changed since the launch?

The core vision is still there, the practical model has changed. Initially it was focused on these six-week courses or intensive weekends. But we noticed people would sign up but not be able to go every week. So we incorporated more individual classes in the evening. But the quality and intellectual breadth of the content hasn’t altered.

Tell me about the Sunday Sermons.

I think there was a recognition that people love community and ideas, and there’s something wonderful about the sermon tradition, but we wanted to do it for the modern age. And they’ve been packed out since we launched it. I could never have predicted that public hunger for ideas.

Do you think the School of Life is a community?

I think people come not just to get good ideas for their lives, but because it makes them feel they’re not alone. People turn up and realise there’s a large group of like-minded people who care about how to deal with the dilemmas of life. The hunger for shared community is part of the grand transformation that’s happening now – the escape from extreme individualism and the age of introspection, and the recognition we need to nurture our social and communal selves. It’s happening in many forms – in philosophy clubs, in Transition Towns, and so on.

People have criticised the School of Life as being a bit commercial, a bit lifestyle-obsessed.

I don’t think it’s commercial, it’s driven by ideas. But it doesn’t necessarily yet have as much of a collective ethos to it as it could have, that strong sense of collective ownership among the people who attend. If The School of Life is going to thrive in the long term, I think it needs to develop that. Is The School of Life a community? Yes, but not yet fully realized. You often see the same people coming to classes, sermons etc, but they’re not necessarily creating their own self-sustaining communities once they step back outside the door.

How involved are you in the School now?

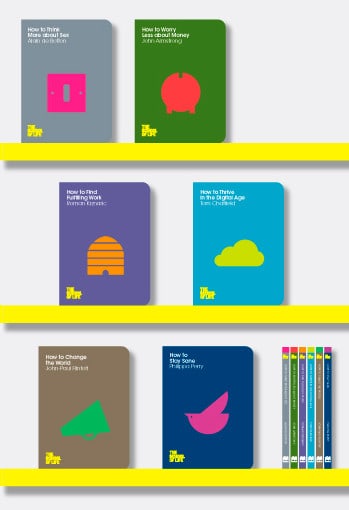

Not hugely involved right at the moment because I’m working on a new book. But I still teach classes and courses, and am involved in some of the larger events we do, such as conversations with visiting thinkers like the recent interview I did with Brené Brown at Conway Hall. I also authored one of the School’s six new self-help books, on How to Find Fulfilling Work, and went on tour with my fellow authors. I understand the School is going to be opening branches in Australia, Brazil, and the US over the next year or so, although I’m not directly involved in that.

Not hugely involved right at the moment because I’m working on a new book. But I still teach classes and courses, and am involved in some of the larger events we do, such as conversations with visiting thinkers like the recent interview I did with Brené Brown at Conway Hall. I also authored one of the School’s six new self-help books, on How to Find Fulfilling Work, and went on tour with my fellow authors. I understand the School is going to be opening branches in Australia, Brazil, and the US over the next year or so, although I’m not directly involved in that.

So how do you think the practical / grassroots philosophy movement will grow?

I think the great task of philosophy clubs is to turn into collective movements of social change, which are capable of tackling the great problems of our age. Look at what they did in the past – at how the Circle of Tchaikovsky in 19th century Russia drew thinkers together and helped to inspire socialist and anarchist movements. That’s the potential of philosophy clubs – they need to escape the obsession with lifestyle. I think we need to wean ourselves off the contemporary obsession with happiness. It’s framed in too individualistic terms. I think we’re going through a great revolution in our understanding of the self, and are realising we’re wired for empathy and mutual aid. If we just obsesses about our own lifestyles, I don’t think we’ll get very far.

Do you think philosophy clubs could help tackle climate change, for example?

I think of our failure to tackle climate change as an empathic failure. It’s a failure to step into the shoes of other people today – especially in developing countries who are suffering the impacts of climate change – and of future generations. We’re hopeless at empathising with people who will be alive in 2100. I’m going to continue my work on empathy to try and contribute to that grander project.

You’re planning to set up an empathy museum?

Yes, it will be the world’s first. We need new institutions in public culture. The Empathy Museum may start by existing online, offering downloadable exhibits. I’m interested in the Human Library Movement, which began in Denmark in 2000. You go along to the library on a certain day, but instead of borrowing a book, you borrow a person for conversation, who tells you their story and answers your questions about their life. I’d like to create a downloadable kit so you can put on events like Human Libraries or Conversation Meals in your own community, school or organisation. Then the museum can be put on everywhere by everyone. It breaks down the old static model of the museum and makes it more participatory.

I’m also an advocate for teaching empathy in schools. And perhaps the next revolution for practical philosophy, which grew up outside of university, is to take it back into universities. They need to be reinvented.

This interview was done as part of Jules Evans’s research project into grassroots philosophy clubs, which will eventually be found at www.thephilosophyhub.com, with interviews with several other pioneers of grassroots philosophy, and a global map of philosophy clubs.